Robert Murray McCheyne Was Wrong!

The quest for sustainable personal Bible reading...

It’s the first of January and so attention is drawn inevitably to Bible Reading Plans. You’ve gone for “stretching”, hoping you’ll do better than last year. January was good, February was patchy, March was tokenistic and April was too busy. The mantra keeps going around in your head that, “good little Christians read the whole Bible in a year, every year”. 66 Books, 1,189 chapters, 31,102 verses, 757,000 words, daunting but surely possible. You’ve even bought a new journaling Bible, highlighters, sticky labels, bookmarks and an artisan motivational propelling pencil. And so, Genesis 1:1, ‘In the beginning…’, so far so good. But in all honesty you know Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy are just over the horizon, lurking like a Bible reading traffic calming measure ready to slow you to a standstill. The Robert Murray McCheyne Reading Plan card all shiny and laminated lures you in with Genesis, Psalms and Matthew but you know even if you traverse the Pentateuch, 1 Chronicles, Jeremiah and Isaiah are waiting to pounce. They’ve tripped you up before even in your good years.

So I want to ask the question, was Robert Murray McCheyne right? Is he not just setting people on a trajectory towards guilt-laden defeat? Is reading 4 chapters at break-neck speed doing anything for you except encouraging you to legalistically skim the surface? This cannot be the optimal way to engage with the Bible, can it? Isn’t it time someone just torpedoed this age old practice that has failed more people than it has helped?

At this pivotal time of the year, please read the below to maybe hear a transformative way to read the Bible in a joyful, nourishing and transformative way. A way that may serve you well and free you from guilt, duty, tickboxes and the Sisyphean Task that your personal Bible reading has regularly become.

The name Robert Murray McCheyne commands immediate respect in evangelical circles, and rightly so. His devotion to Christ, his pastoral heart, his early death at twenty-nine after pouring himself out in ministry. These facts alone secure him a place among the great saints. His Bible reading plan, designed in 1842 to take believers through the Old Testament once and the New Testament and Psalms twice each year, has become one of the most widely used spiritual disciplines in Protestant Christianity. Millions have attempted it. Most have failed. And here I must say something that feels almost sacrilegious: I think McCheyne was wrong. Not about the authority of Scripture. Not about the necessity of reading God’s word. But about the method. The mysticism that good Christians read their Bible cover to cover each year is an unhelpful myth that burdens people unnecessarily, defeats them repeatedly, and puts far too much pressure on January.

Let me be clear from the outset. Reading God’s word is absolutely essential. No Christian worth the name would dispute this. Scripture is God-breathed, profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for training in righteousness. It is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword. It is the means by which the Spirit sanctifies believers, the lamp to our feet and light to our path. Without regular engagement with the Bible, our faith withers. Our prayers become aimless. Our theology drifts toward whatever winds of doctrine happen to be blowing through our culture at any given moment. The question is not whether we should read Scripture. The question is how.

McCheyne’s plan emerged from genuine pastoral concern. He wanted his congregation at St Peter’s in Dundee to know the whole counsel of God. He wanted them immersed in Scripture daily. These are good desires. Laudable desires. But somewhere between McCheyne’s original intention and our contemporary practice, his plan became less a helpful tool and more a spiritual metric, a way of measuring devotion, a badge of serious Christianity. You meet someone at church and mention you’re doing the McCheyne plan. Their eyes light up with recognition and respect. You meet someone and admit you’re not following any particular plan, just reading a bit here and there. The response is more muted. Less impressed. There’s an unspoken hierarchy at work.

This is where the burden begins. January arrives with its customary promises of renewal and fresh starts. Believers purchase new journals, sharpen pencils, download apps, and commit themselves once more to getting through the entire Bible in twelve months. For approximately three weeks, things go well. Then February arrives. Life intrudes. A sick child. A work deadline. A bout of flu. Suddenly they’re five days behind. Then ten. Then they’re still slogging through Leviticus in March while the plan says they should be in Judges.

What happens next is drearily predictable. Guilt sets in. The voice of condemnation whispers that real Christians, serious Christians, committed Christians don’t fall behind. They don’t skip days. They don’t find the genealogies tedious or the ceremonial laws bewildering. For real Christians every ‘quiet time’ is exhilaratingly refreshing. The believer tries to catch up, reading multiple days’ worth of chapters in one sitting, eyes glazing over as they race through passages, desperate to tick boxes rather than encounter the living God. Eventually, many simply give up. They abandon the plan entirely, often abandoning consistent Bible reading altogether, defeated by a system that promised blessing but delivered only frustration.

The problem is not laziness. The problem is not lack of devotion. The problem is that the Bible does not yield its treasure to hasty enquiry, to rapid coverage, to the kind of superficial engagement that treating it like a checklist inevitably produces. Scripture is not a book to be conquered, a mountain to be summited so we can plant our flag at the top and feel accomplished. It is a library of sixty-six books, written over fifteen hundred years, in three languages, spanning multiple genres, addressing countless situations, revealing one magnificent story of God’s redemptive purposes in Jesus Christ. This kind of literature requires something other than speed reading.

Think about how we approach other great books. Suppose you wanted to understand Shakespeare. Would you read all thirty-seven plays in a year, racing through one every nine or ten days? Or would you take a single play, perhaps Hamlet, and read it multiple times? You’d read it once for the plot. Again for the characters. A third time for the language. A fourth time noticing the themes. You’d read scholarly introductions. You’d watch performances. You’d memorise soliloquies. By the end of this process, Hamlet would be inside you. Its phrases would surface in your mind unbidden. You’d understand not just what happens but why it matters. You’d see connections and patterns that completely escaped you on first reading. The play would have become part of your mental furniture, shaping how you think about revenge, madness, mortality, duty.

This is what I’m proposing for Scripture. Better to pick a single book and get massively familiar with it through repeated, consistent reading. Choose Philippians, for instance. It’s four chapters. You could read the entire letter in fifteen minutes. Now read it every day for a month. Then for another month. Then for a third. What happens? Initially, you notice the basic content. Paul is in prison. He’s writing to a church he loves. He’s joyful despite his circumstances. But keep reading. You start noticing the structure. The recurring themes. The way Paul deals with conflict. His theology of suffering. His Christology in chapter two. The warning against false teachers. The personal notes about Timothy and Epaphroditus aren’t just filler but wonderfully instructive. His own testimony about counting everything as loss compared to knowing Christ.

Read it for three months. Now you’re noticing tiny details. The way Paul uses specific words. The Old Testament echoes. The grammar. The flow of argument. The pastoral wisdom in how he addresses problems without crushing people. You’re seeing how the rejoicing he commands isn’t superficial optimism but something deeper, rooted in confidence about God’s purposes. The famous passage about joy and peace isn’t a mere pep talk but emerges from a carefully constructed theological vision. By now, you know this letter. Really know it. You can close your eyes and recall whole sections. You can quote verses in context. You understand not just the words but the world behind the words.

And here’s what else happens. This deep, repeated reading enables believers to see, understand and comprehend things that simply never occur from superficial skim reading. You notice that Paul’s imprisonment isn’t incidental to the letter but central to its message. You see the structure more clearly: the thanksgiving, the prayer, the narrative section, the exhortations. You grasp how the hymn in chapter two functions within Paul’s argument about unity. You understand why the warning in chapter three is so sharp. The letter stops being a collection of isolated verses and becomes an integrated whole, a coherent argument, a window into apostolic Christianity.

Moreover, something remarkable happens in your mind. The book becomes so familiar that it starts working even when you’re not actually reading it. You’re in a difficult situation at work and suddenly you’re thinking about Paul’s words on considering others more significant than yourselves. You’re facing opposition and you remember the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus. You’re anxious about something and before you even consciously recall it, the words about not being anxious but presenting requests to God are shaping your response. This is Scripture doing what it’s meant to do, not merely informing your mind but transforming your heart, not just adding to your knowledge but shaping your character.

The McCheyne approach, for all its good intentions, rarely produces this kind of deep familiarity. How could it? You read Philippians once during the year, probably split across several days’ readings mixed with other passages, and then you move on. Next year you’ll read it again, but twelve months is a long time. The details have faded. You’re essentially starting over. You gain breadth but sacrifice depth. You can say you’ve read the whole Bible, but have you really encountered it? Has it gotten inside you? Or have you merely passed your eyes over the words?

There’s also the tyranny of the calendar to consider. McCheyne’s plan puts enormous pressure on January. It’s the time to start fresh, to begin again, to get it right this time. But this means that failure in January can poison the entire year. You fall behind early and spend eleven months feeling guilty. What if we abandoned this tyranny? What if we recognised that in the Christian life, we have multiple Mondays on which to begin again? Every morning is a new mercy. Every day offers a fresh start. Miss a day of reading? Simply pick up where you left off. No guilt. No frantic catching up. No sense that you’ve ruined everything and might as well quit. No suspicion that you might not be a real Christian because you have a bad month of May.

This approach is both more realistic and more grace-filled. Life is unpredictable. There will be days when you don’t read your Bible. Sick days. Crisis days. Days when you’re so exhausted that you fall into bed without even thinking about your Bible. This is not spiritual failure. This is being human. God understands our frame and remembers that we are dust. He doesn’t demand unbroken streaks of perfect consistency, this isn’t Candy Crush. He invites us to feast on His word, to delight in His law, to hide it in our hearts. None of this requires maintaining a perfect record.

The principle here is simple but profound. Some Bible reading is better than none. This seems almost embarrassingly obvious, yet the McCheyne mystique often suggests the opposite. It creates an all or nothing mentality. Either you’re doing the plan, keeping up with the schedule, getting through the whole Bible, or you’re failing. This is simply false. Five minutes with one psalm, really prayed and pondered, is worth far more than racing through four chapters you barely remember. Ten minutes in John’s Gospel, carefully considered, will do more for your soul than forty-five minutes of checkbox reading through 1 Corinthians.

Let me address an obvious objection. Doesn’t focusing on one book mean we’ll neglect other parts of Scripture? Won’t we become doctrinally unbalanced? Won’t we miss important truths found only in books we never read? These are fair concerns, but they’re not as serious as they first appear. First, nobody is suggesting we read only one book of the Bible for our entire lives. We’re talking about seasons of deep focus. After three months immersed in Philippians, move to Micah. Then perhaps to one of the Gospels. Then to Ecclesiastes. Over time, you’ll cover significant portions of Scripture, but you’ll actually know these books rather than merely having read them once. It’s the difference between making a friend for life and saying good morning to the person you pass in the street walking their miniature Schnauzer one morning.

Second, the concern about doctrinal balance assumes that rapid coverage somehow produces better theology than deep engagement. This is questionable. Most Christians who follow Gen-Rev reading plans don’t extract and synthesise theological content as they go. They read, move on, and forget. The person who deeply knows Philippians, understanding its theology of Christ, its ethics of humility, its perspective on suffering, is likely to have a richer theological framework than someone who read it once last March mixed in with three other passages.

Third, we don’t receive our theology from private reading alone. We’re part of churches where Scripture is preached and taught. We read books by wise theologians. We discuss Scripture with other believers. We’re not isolated individuals constructing systematic theology from scratch through personal Bible reading. Our individual reading fits within this larger ecology of learning. Deep knowledge of some books combined with the teaching ministry of the church is more than sufficient to produce robust, biblical Christianity.

There’s another advantage to the approach I’m recommending. It’s more conducive to memorisation. When you’re reading the same book repeatedly, memorising becomes natural. You’re not trying to memorise isolated verses from across the canon. You’re learning whole passages from a book you’re deeply familiar with. The verses stay in your mind because they’re anchored in context. You know what comes before and after. You understand how they fit into the argument. This kind of memorisation is sturdier and more useful than collecting random verses.

Furthermore, repeated reading of one book allows you to move beyond merely understanding what the text says to asking deeper questions. Why does Paul structure his argument this way? Why does he use this particular metaphor? Why does he address this issue before that one? What does this reveal about his pastoral approach? What does it teach us about the church he’s addressing? These aren’t questions you can meaningfully engage when you’re rushing through to stay on schedule. They require time, attention, meditation. They’re the questions that produce genuine insight.

I’m aware that suggesting McCheyne was wrong feels provocative, even irreverent. He was a godly man who loved Scripture and wanted others to love it too. But we’re not required to believe that every spiritual discipline from the past, no matter how well-intentioned, is above criticism or improvement. We’re allowed to ask whether a particular method actually achieves its stated goals or whether it might inadvertently produce different results. We’re allowed to notice that something can be good in theory but problematic in practice.

The McCheyne plan works wonderfully for some people. They have the time, the discipline, the reading speed, and the mental capacity to maintain the schedule year after year. If you’re one of these people, crack on. What I’m objecting to is the notion that this is the standard, the measure of devotion, the mark of serious Christianity. It isn’t. It’s one method among many. For a great many believers, perhaps even most, it’s not the most effective method.

What I’m proposing is actually more demanding in some ways. It’s easier to skim-read four chapters, tick a box, and feel a sense of accomplishment, than to read the same chapter for the thirtieth time and force yourself to notice something new. It’s easier to maintain variety, constantly encountering new material, than to stay with one book until you really know it. Depth requires patience. Familiarity requires persistence. But the rewards are immense. You end up with portions of Scripture that are truly yours, that have shaped your thinking, that rise to your mind when you need them, that inform your prayers and your decisions.

This approach also respects the literary character of Scripture. The books of the Bible are not arbitrary collections of verses. They’re carefully composed works with structure, development, and purpose. Reading them as coherent wholes, repeatedly, allows us to appreciate them as literature and not merely as theological databases. We encounter the artistry of the biblical authors, the way they build arguments, the metaphors they choose, the rhetorical strategies they employ. This enriches our reading immeasurably.

Consider the Gospels. How many Christians have read all four Gospels but couldn’t tell you what’s distinctive about each one? They’ve read them, yes, but as part of a reading plan that has them bouncing between Old Testament, New Testament, and Psalms. What if instead you spent a year with Mark? You’d come to see his urgency, his focus on action, his presentation of Jesus as the suffering Son of God. You’d notice how he structures his narrative. You’d see the discipleship themes. You’d understand why he includes certain details and omits others. This Gospel would become part of you in a way that reading it once as part of a comprehensive plan simply cannot achieve.

Or take the Psalms. Many reading plans have you reading a psalm or two each day alongside other passages. This isn’t bad. But what if you thought about the same ten psalms every day for a month? Then the next ten the following month? You’d learn the contours of biblical lament. You’d see the structure of praise. You’d notice the theology embedded in worship. These psalms would become your prayers, rising to your lips in circumstances the psalmists never imagined but which nevertheless fit the patterns of human experience they captured.

The question of pressure and burden is particularly important. Christianity is not meant to be oppressive. Jesus said His yoke is easy and His burden light. Paul wrote about the glorious freedom of the children of God. Yet somehow we’ve created spiritual disciplines that leave people feeling perpetually inadequate. They’re behind on their reading plan. They haven’t prayed enough. They’re not witnessing enough. They’re not serving enough. They’re not giving enough. The Christian life becomes an endless treadmill of duties that can never quite be fulfilled. This is not the gospel. This is not freedom.

Reading Scripture should be a delight, not a duty. Yes, there’s discipline involved. Yes, we must do it even when we don’t feel like it. But the fundamental posture should be desire, not drudgery. We should open our Bibles eagerly, anticipating encounter with God through His word. When Bible reading becomes primarily about maintaining a schedule, checking boxes, and avoiding the guilt of falling behind, something has gone badly wrong. We’ve turned a means of grace into a measure of performance.

The approach I’m advocating recovers the joy of Scripture. You’re not reading to finish. You’re reading to know. You’re not racing through to say you’ve done it. You’re lingering, pondering, returning. There’s no pressure because there’s no schedule to maintain. There’s no failure because you can’t fall behind. You simply continue where you are, day by day, reading and rereading until the word becomes part of you.

This method also has the advantage of being adaptable to different life seasons. When life is calmer, you might read your chosen book twice a day. When things are chaotic, once. During particularly difficult periods, perhaps you just read a single chapter repeatedly. The method flexes with your circumstances rather than demanding you flex to meet its requirements. This is pastoral. This is realistic. This is sustainable.

As John Piper so famously said, ‘The Lord allowed the invention of social media to prove to us that we really do have time to read our Bibles!’

I want to be clear that I’m not opposing systematic reading of Scripture. I’m opposing the particular system that has become dominant and the mystique surrounding it.

I am also not suggesting that we only read books we like or find easy. Sometimes the call of discipleship means persevering through difficult material. But there’s a difference between persevering through difficulty because we’re committed to understanding what God has said and persevering through difficulty because we’re trying to maintain a schedule. The first is profitable. The second is merely exhausting.

What would it look like to structure a year of Bible reading along the lines I’m suggesting? You might spend three months in Romans, reading it daily, perhaps even multiple times per day. The first month you’re getting familiar with the content. The second month you’re noticing patterns and themes. The third month you’re seeing things you never saw before and the letter is becoming part of your mental framework. Then you move to Mark’s Gospel for the next three months. Same process. Deep reading. Repeated engagement. Growing familiarity. Then perhaps Exodus for three months. Then First John. By year’s end, you’ve deeply engaged with four substantial books of Scripture. You actually know them. They’re working in you. This seems far more valuable than having read the entire Bible in a way that left little lasting impact.

The proof, as they say, is in the pudding. Talk to people who’ve followed the McCheyne plan for years. Ask them what they remember from last year’s reading. Ask them to explain Habakkuk or Haggai or Philemon. Ask them how Leviticus has shaped their understanding of holiness or how Ezekiel has informed their eschatology. Many will struggle to answer because they read these books too quickly, without sufficient context, mixed in with too many other things. Now talk to someone who spent six months reading and rereading Joshua. They can tell you the structure. They can explain the theology. They can show you how it’s changed their understanding of the church. This is the fruit of depth.

McCheyne’s plan has endured for over 180 years. It has undoubtedly helped many believers develop consistent reading habits. For this we should be grateful. But longevity doesn’t equal unquestionable validity. The question is not whether the plan has value but whether it’s the best approach for most Christians in most circumstances. I don’t believe it is. I think we can do better. I think we should do better.

The Bible itself doesn’t prescribe a reading plan. It commands us to meditate on God’s law day and night, to let the word dwell in us richly, to be people who tremble at God’s word. None of this suggests rapid reading of maximal content. Rather, it suggests deep engagement, careful attention, prolonged meditation. The Psalms praise the person who delights in God’s law and meditates on it constantly. This is not skim reading. This is not box checking. This is love. The word for meditate is literally the word ‘chew’, to ‘ruminate’.

Perhaps the real issue is that we’ve become addicted to completion, to finishing things, to achievement. We live in a culture obsessed with productivity, efficiency, and quantifiable results. These values have infected our spirituality. We want to finish the Bible like we want to finish a project at work. We want to tick it off our list. We want the sense of accomplishment. But spiritual growth doesn’t work this way. You can’t gamify sanctification. You can’t metrics-driven your way to Christlikeness.

What if we gave ourselves permission to slow down? To stay in one place until we’ve genuinely encountered God there? To reread until we really understand? To memorise until the words are ours? To meditate until truth has penetrated not just our minds but our hearts? This feels countercultural. It feels inefficient. But it might be exactly what we need.

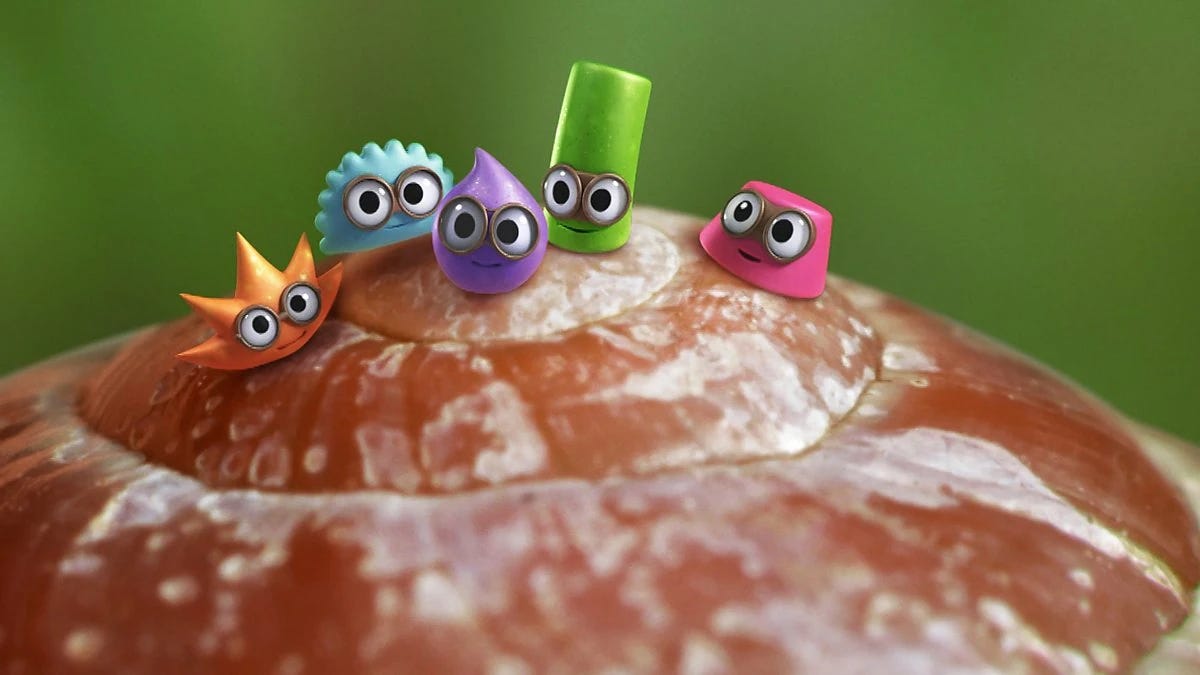

My son Isaac, loves watching a sweet little TV series called Tiny Wonders with The Noglins. In in little creatures land on an everyday object and explore it thoroughly. The catchphrase of the show is, ‘Slow Down, Look Closer.’ I think we should listen to Fidd, Nono, Itty, Yapp-Yapp, and Hum, when it comes other our Bible Reading habits.

I imagine McCheyne himself, were he here, might understand this. He was a man who loved Scripture deeply, who preached it powerfully, who lived it authentically. His plan was meant to serve encounter with God, not to become an end in itself. If the plan has become an obstacle rather than an aid, if it burdens rather than blesses, if it produces guilt rather than growth, perhaps it’s time to honour McCheyne’s intention by abandoning his method.

We need the whole counsel of God. We need to know what Scripture teaches across its breadth and depth. But we don’t need to acquire this knowledge in a single year through a forced march from Genesis to Revelation. We have our whole lives to grow in understanding of God’s word. Why the hurry? Why the pressure? Why the guilt when we can’t maintain an arbitrary schedule designed in 1842 for a congregation in Scotland whose life circumstances bore little resemblance to ours?

Better to know some Scripture deeply than all Scripture superficially. Better to have Philippians so thoroughly embedded in your mind that it shapes your instinctive responses than to have read it once last March and barely remember it. Better to encounter God meaningfully in Mark’s Gospel over months of repeated reading than to race through all four Gospels in a blur of chapters that blend together. Better to be transformed by deep engagement than merely informed by rapid coverage.

The Christian life is not a sprint. It’s not even a marathon. It’s a lifelong journey of growing in grace and knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. We need approaches to Scripture reading that recognise this, that build sustainable habits, that produce genuine transformation, that facilitate real encounter with God through His word. For many believers, perhaps most, the annual cover-to-cover approach doesn’t achieve these goals. We need something better.

We need to stop measuring devotion by how much we’ve read and start measuring it by how deeply the word has penetrated. We need to stop feeling guilty about falling behind on schedules and start celebrating consistent engagement, however modest. We need to stop treating the Bible like a book to be conquered and start treating it like a garden to be explored repeatedly, finding new fruit each time we return. We need wisdom more than we need velocity.

I think Robert Murray McCheyne was wrong. Not about everything. Not even about most things. But about this. The plan that bears his name, whatever its original merits, has become an unhelpful myth that hinders more than it helps. It’s time we said so. It’s time we gave ourselves and others permission to read differently. Some Bible reading is better than none. Deep Bible reading is better than broad Bible reading. Sustainable Bible reading is better than guilt-inducing Bible reading. And consistent engagement with books we’re coming to know intimately is better than annual sprints through the entire canon that leave us exhausted and defeated every February.

This is not a call to read less Scripture. It’s a call to read it better. To read it more deeply. To read it more sustainably. To read it in ways that actually transform us rather than merely inform us. To recover what the Puritans called closeness with the text, that intimate familiarity that comes from living with portions of Scripture until they live in us. This is what we need. This is what will actually make us people of the book.

Bon Appétit in 2026…

Thank you for writing this. I read somewhere the intention of McCheyne's plan was for head of households read the first two passages personally in the morning and then for family worship read the last two passages with their children. Thomas Manton, writing in the 1600's, wrote in his observation the reason for the decline in society was because families no longer worshiped four times a day. In our day, 2026, there are many Christians who struggle with worshipping God one day a week; better yet, one hour on one day of the week.

McCheyne was not wrong, and neither are you. I have used McCheyne's reading plan for the last 10-15 years and God has used it to reveal wonderful truths. I have also spent time in individual books studying them at length; which, once again, God has used to reveal wonderful truths.

The best way to engage the Word of God is the one that will get you to engage with the Word of God. The Holy Spirit will use either one, not because we are faithful to do it, but because He is faithful to fulfill His promises. He beckons all who are thirsty to come to the waters and drink, and like the rain and snow that water the earth, His word does not return to Him empty, but accomplishes what He purposes. (Isaiah 55)

This article reads like AI.

The fact that the M'Cheyne plan has endured for 180 years should not be so lightly dismissed. Nor the checking of boxes, etc. I've personally never used the plan. For the last several years, I've used a plan that takes you through the Bible every 88 days. That's about 40-50 minutes of reading per day for the average reader. There is enormous value in immersing yourself in the Word--all of the Word--systematically. One could easily do what you hold out as better here, i.e., spending a month or three in one book, alongside a plan like M'Cheyne, which I believe takes about 15 minutes of reading per day to complete.

Currently, I'm using the Horner plan, which involves reading 10 chapters each day from all over the Bible. I'm loving it, and I'm seeing the interlacing of Scripture in ways I've never experienced before. But that isn't all I'm doing. We're "deep-diving" through Matthew in family worship; we're memorizing Isaiah 55 (and keeping fresh about a dozen other passages) as a family; we're working through Philippians and 1 Samuel each week in corporate worship, etc.

I think your article is unnecessarily critical of a system of Bible reading that has served countless Christians well for decades upon decades.